Today’s post contains my favorite photos from the last year—my top 21 photos from 2021. It seems I’ve fallen into an annual tradition of selecting and sharing my favorite photos from the year. It’s an activity I really enjoy. It’s so easy to click through a year’s worth of digital photos—so much easier than viewing the slides from my early days in photography.

It’s fun to look back through my photos and remember the highlights of the year. But the thing that makes this activity really special is rediscovering shots I’d forgotten about—like this Northern Cardinal (Cardinalis cardinalis) enjoying the water in our birdbath. Did you know the name of these birds refers to the cardinals of the Roman Catholic Church who wear distinctive red robes and caps?

It’s fun to look back through my photos and remember the highlights of the year. But the thing that makes this activity really special is rediscovering shots I’d forgotten about—like this Northern Cardinal (Cardinalis cardinalis) enjoying the water in our birdbath. Did you know the name of these birds refers to the cardinals of the Roman Catholic Church who wear distinctive red robes and caps?

1. Northern Cardinal in Birdbath

Here’s another photo I’d forgotten. This darling Carolina Chickadee (Poecile carolinensis) was busy gathering berries. It took quite a few shots to catch this perfect pose.

2. Carolina Chickadee with Berry

In keeping with the bird theme, the below photo was my favorite from a visit to Swan Lake Iris Gardens back in May. This park, in Sumter, South Carolina, is home to all eight known species of swan. This is a Black Swan (Cygnus atratus). There’s a fascinating story about black swans that I first shared in my blog post Stately Swans and their Surprising Stories.

In keeping with the bird theme, the below photo was my favorite from a visit to Swan Lake Iris Gardens back in May. This park, in Sumter, South Carolina, is home to all eight known species of swan. This is a Black Swan (Cygnus atratus). There’s a fascinating story about black swans that I first shared in my blog post Stately Swans and their Surprising Stories.

Interestingly, before 1697, Europeans were so convinced all swans were white that they used the expression “black swan” to describe something that was impossible. After the first Europeans witnessed the black swans of Australia, the expression morphed to represent the fragility of any system of thought. Nowadays, the term “Black Swans”, as defined by author Nassim Nicholas Taleb, has evolved to represent events which are rare, have extreme impact, and have retrospective predictability.

3. Black Swan with Head Tucked In

A surprising (well… maybe not that surprising) number of my photos are of flowers. This is my favorite from the last year—a series of blooms on the Clematis ‘Ramona Blue’ in our flower garden.

4. Four Clematis ‘Ramona Blue’ Blooms

Another flower, the sunflower, featured prominently in my blog post In the Sunflower Field. These flowers are so bright and cheery they are bound to put a smile on one’s face. They are also a magnet for butterflies and bees. Two of my favorite shots came from my visit to the local U-Pick sunflower field.

Check out this Common Buckeye (Junonia coenia) sitting pretty on a sunflower bloom. It’s like a little winged work of art!

5. Common Buckeye Butterfly on Sunflower

This next shot almost looks staged—an Eastern Tiger Swallowtail and a bee on a single perfect sunflower head in front of billowing grass seed heads and a soft blue sky.

6. Eastern Tiger Swallowtail and Bee on Sunflower

Another one of my favorite shots came from a different local U-pick—a U-pick peach orchard (see A Peach of a Day). While there were zillions of peaches in that orchard, finding the perfect peach, hanging on a tree, with good lighting and a subtle background was not easy. My persistence paid off with this shot. By the way, I love how that little hole in the leaf adds a touch of reality to the photo.

7. Lush Ripe Peach on Tree

Regular readers may recall that I visited family in Nova Scotia this past summer. I had the rare opportunity to spend time exploring that beautiful province with my sister Marian. We had such fun! Several of my favorite photos come from our road trip to Brier Island.

Watching humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) in their natural environment was a highlight of my year! You can read all about this adventure in the blog post Watching Humpbacks on the Bay of Fundy. The below photo shows the tail of a humpback whale raised above the water. The whale does this before diving to propel itself down in a steep descend. A whale’s tail roll, as it’s commonly called, is awe-inspiring to witness in person.

8. Humpback Whale Tail Roll

As impressive as the tail rolls were, seeing humpback whales breach—leap out of the water head first—was absolutely incredible!

9. Humpback Whale Breaching

Another one of the many beautiful and fascinating sights we enjoyed on our Nova Scotia road trip was Balancing Rock in Tiverton. This 20-foot finger of volcanic rock, estimated to weigh 20 tonnes or more, is balanced precariously on the edge of the rock below. You can read more about it in the blog post Solid as a Rock.

10. Balancing Rock in Tiverton Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia is nearly surrounded by the ocean. Only a narrow stretch of land, called the Chignecto Isthmus, prevents it from being an island. As a result, fog is common. It’s a shutter bug’s dream—ruggedly beautiful coastlines shrouded in dense misty fog! These rocky cliffs are in the Nature Conservancy of Canada Reserve on Brier Island’s west coast.

11. Foggy Coastline of Brier Island

Not all of Nova Scotia’s coastline is rocky. The shores of the Bay of Fundy, which I described in the blog post We Dined on the Ocean Floor, are vast intertidal zones revealing beaches of soggy sand, rocks and mud at low tide. This is one of my favorite photos from Burntcoat Head where we dined on the ocean floor.

12. Picnic at Burntcoat Head

The charming town of Parrsboro is also located along the Bay of Fundy. I raved about Parrsboro, as well as Chester, Nova Scotia and Victoria, Prince Edward Island in my blog post Strolling Through a Picture Postcard. I love the contrast between the long, flat shore and the billowy, soft clouds in this view from Partridge Island.

13. View from Partridge Island

With its proximity to the sea, fishing and other sea-faring industries play a major role in Nova Scotia’s economy. This dramatic yellow fishing boat was docked at the Westport wharf in Brier Island.

14. Yellow Fishing Boat at Wharf on Brier Island

Sailing and other water sports are popular pastimes. I spotted this beautiful view at the Chester Yacht Club.

15. Row of White Boats at Chester Yacht Club Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia’s sea-faring roots are honored in a number of museums and historical attractions. Sherbrooke Village Museum represents the 1860s when timber, tall ships and gold led to that community’s prosperity. It’s a living museum with actors, dressed in period costume, performing their daily tasks. This is the storeroom at Cumminger Brothers’ General Store in Sherbrooke Village Museum.

16. Cumminger Brothers’ General Store at Sherbrooke Village

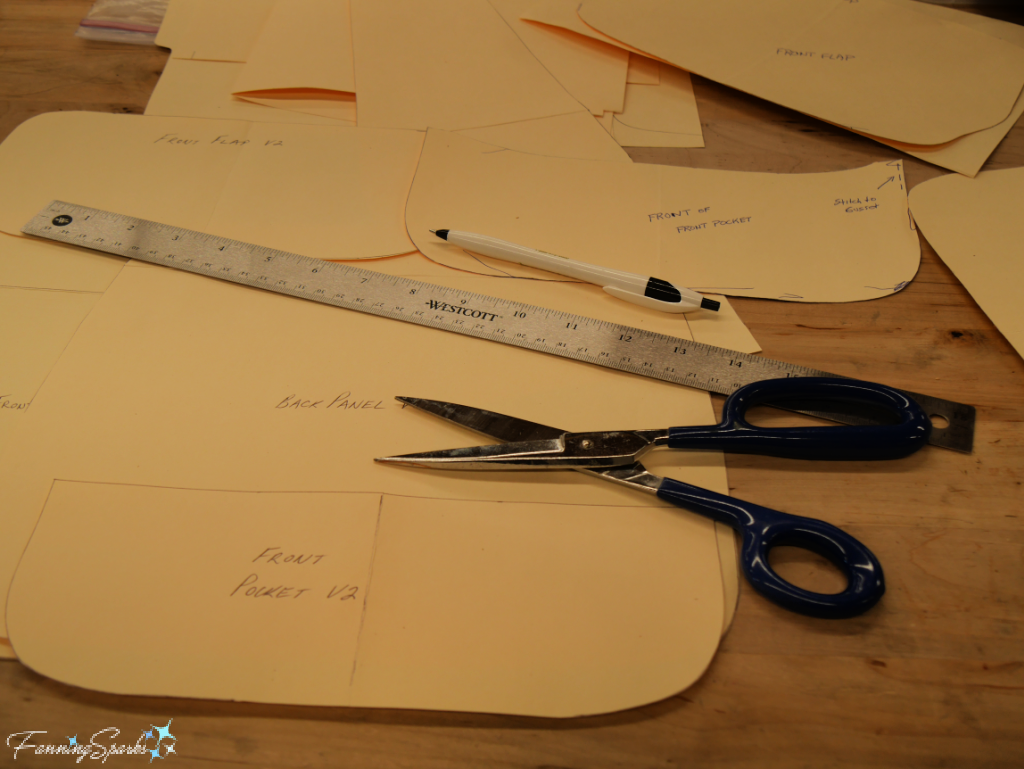

My trip to Nova Scotia provided many opportunities for beautiful photography but it was not the only adventure that had my camera working overtime. In October, I travelled to the John C Campbell Folk School in the mountains of North Carolina where I participated in a Work/Study program. It was six weeks of immersion in the creative magic of the Folk School’s traditional crafts. Here are my favorite photos from that special time.

The extraordinary details of a Shaker-style flat hearth sweeper broom, made by instructor Mark Hendry, are highlighted in the below photo. You can see more of Mark’s work and learn about my experience making brooms in the blog post Swept Away by Broom Making.

17. Stitching on Mark Hendry’s Hearth Sweeper Broom

One of the joys of the Folk School is witnessing the talent of fellow students. I spotted these baskets, made by students in a basketry class, drying in the morning sunlight outside the Rock Room. You can learn about the Rock Room and the other studios in my blog post Folk School Studios-Where the Magic Happens.

18. Baskets Drying Outside Basketry Studio

The interplay between sunlight and shadows makes the below photo a favorite. The hand woven placement, by Crossnore Weavers, was one of My Top 12 Picks from the Folk School Craft Shop.

19. Placemat by Crossnore Weavers with Place Setting

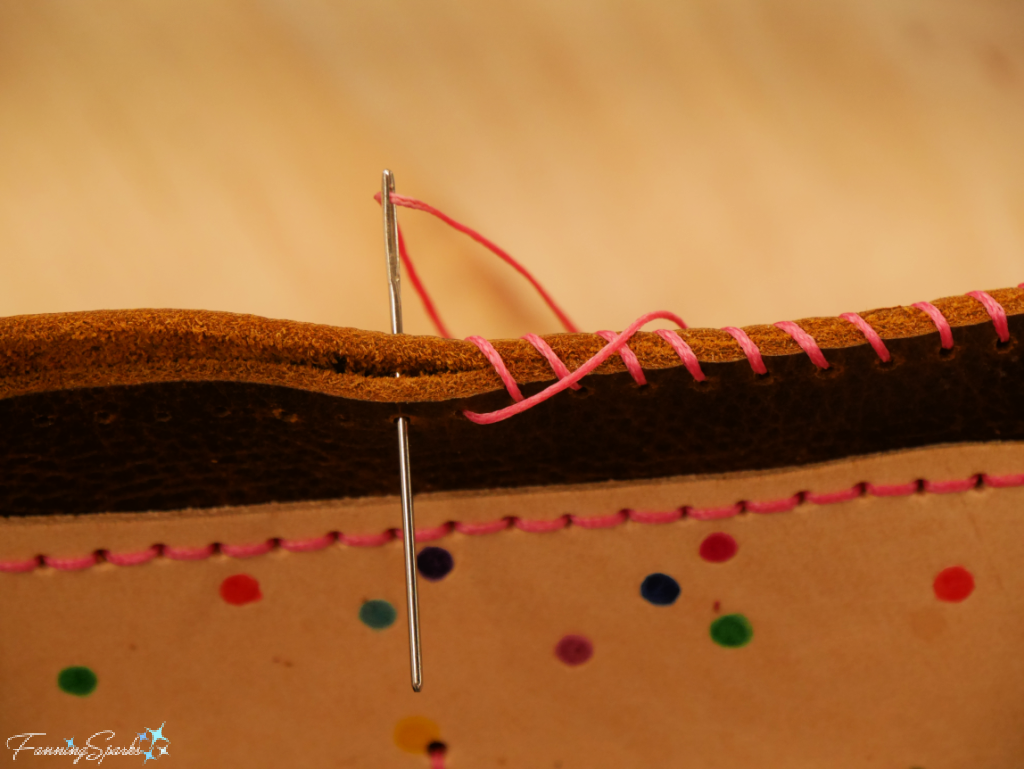

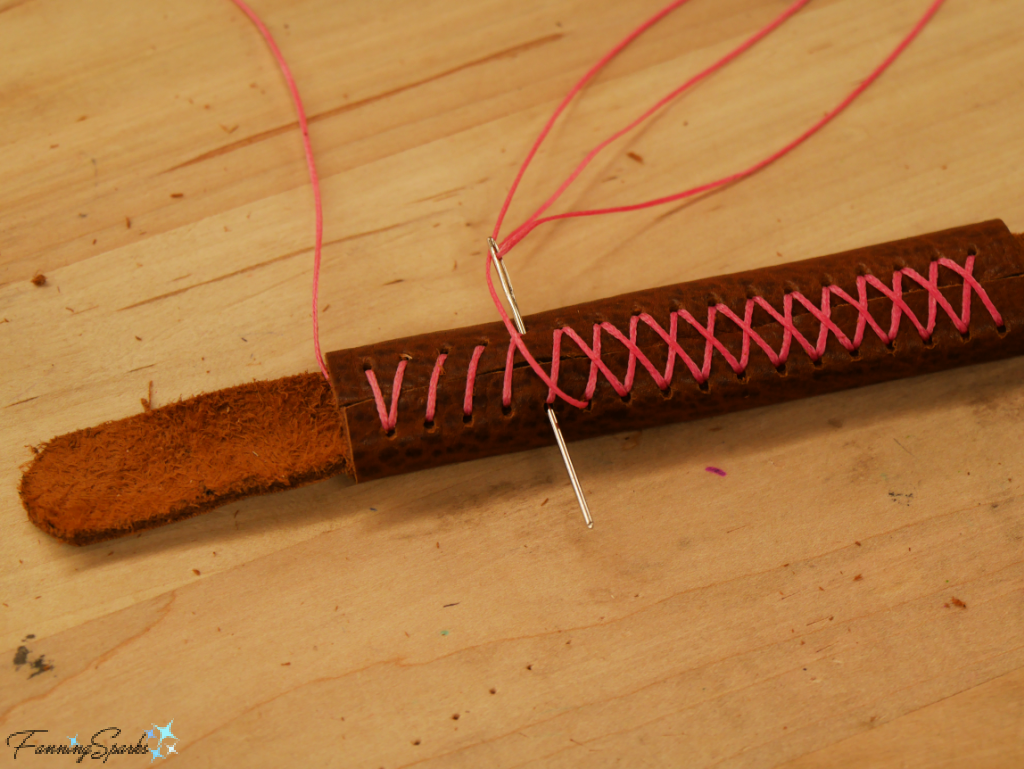

The next photo showcases Tom Slavicek, leather crafting instructor, stitching a beautiful butterfly wing bag. You can see more of Tom’s work and learn about my experience attending his class in the blog post My First Leathercrafting Project.

20. Tom Slavicek Stitches a Leather Butterfly Wing Bag

This brings me to number 21—my final favorite photo from the year. It wasn’t easy to choose a favorite from all the projects I made this last year. But this shot of the teacup pincushion I made from felt and a family heirloom cup and saucer came out on top. Not only is it a sentimental project (see Teacup Pincushion – DIY Tutorial) but I love the styling and lighting in this shot.

21. Teacup Pincushion Embellished with Felt Flowers

I’ve shared numerous photos—about 940 actually—on the FanningSparks’ blog this past year. Considering that I probably take five times that many photos, I’m truly grateful for the convenience of digital photography.

More Info

I hope you’ve enjoyed my favorite photos from 2021. You may also like similar posts from 2019 and 2020:

. Top 19 Photos from 2019

. Top 20 Photos from 2020

Several blog posts were mentioned in today’s post. Here’s a summary list for your convenience:

. Stately Swans and their Surprising Stories

. In the Sunflower Field

. A Peach of a Day

. Watching Humpbacks on the Bay of Fundy

. Solid as a Rock

. We Dined on the Ocean Floor

. Strolling Through a Picture Postcard

. Swept Away by Broom Making

. Folk School Studios-Where the Magic Happens

. My Top 12 Picks from the Folk School Craft Shop

. My First Leathercrafting Project

. Teacup Pincushion – DIY Tutorial

Today’s Takeaways

1. Examining a scene or a subject for the best possible photo may also help you more fully appreciate the moment.

2. It may take several shots to get a photo just right.

3. Looking back through photos is a great way to remember the highlights of the year.

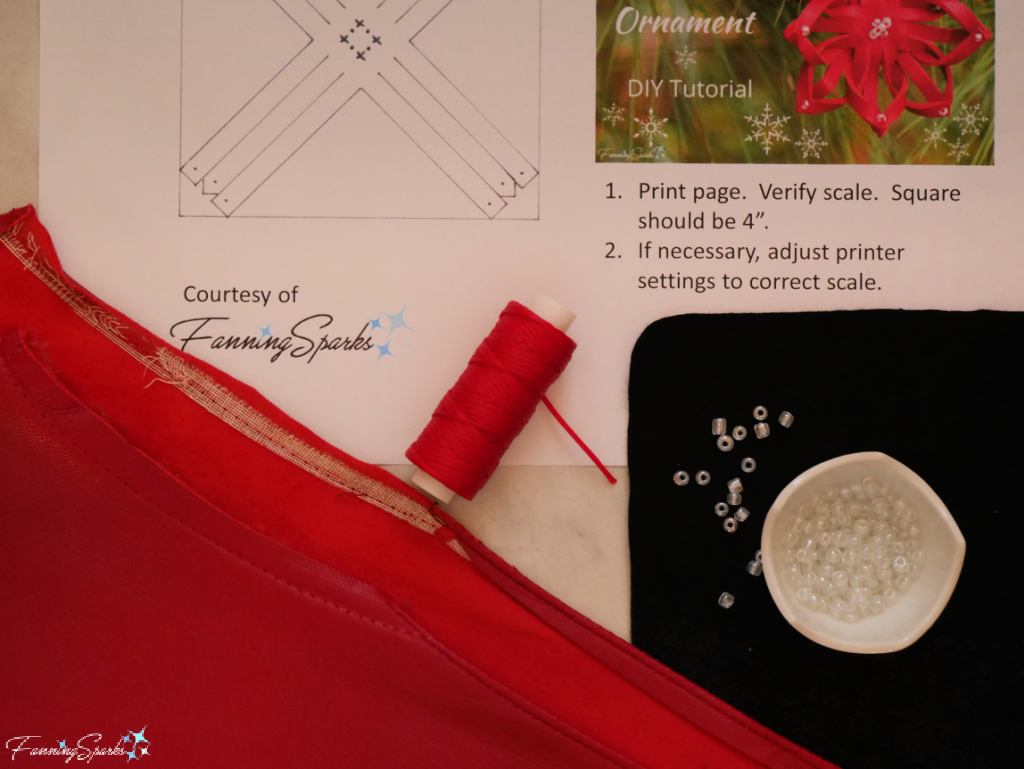

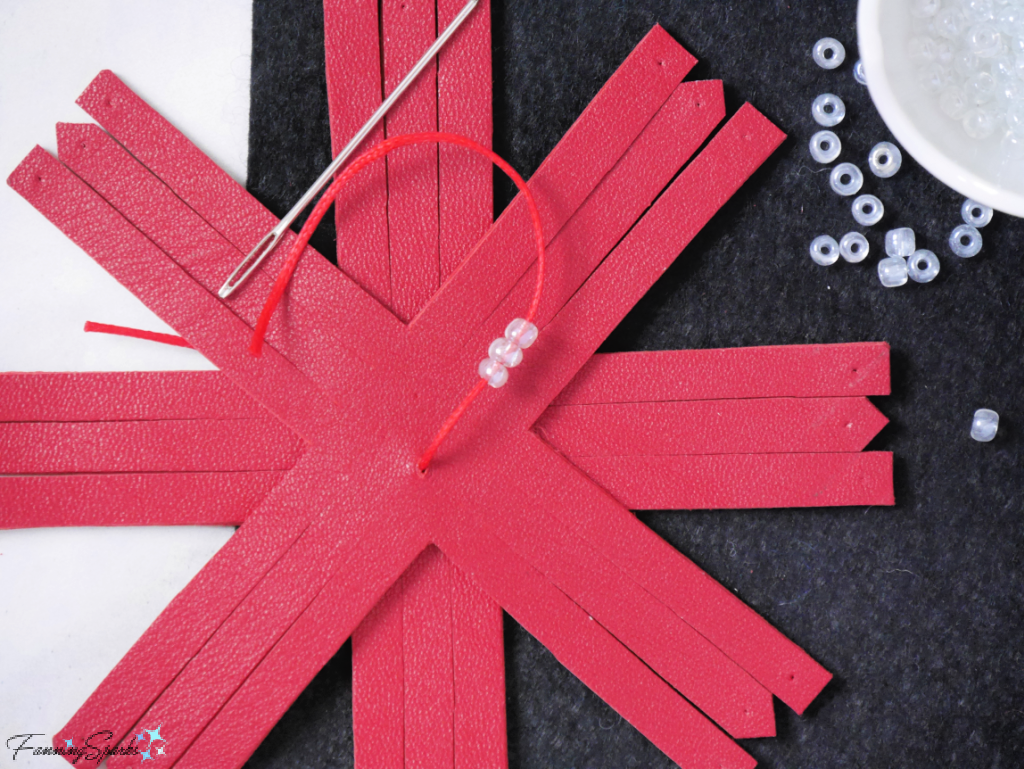

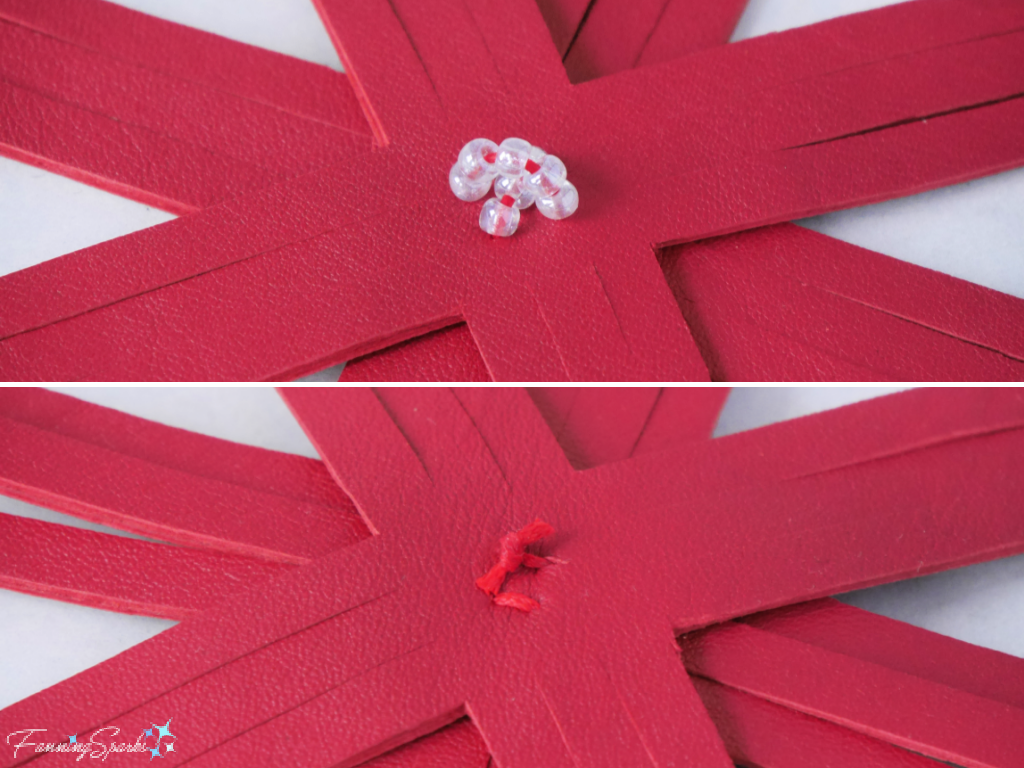

Your new leather snowflake is ready! It looks lovely on the Christmas tree but it would also make a gorgeous gift topper.

Your new leather snowflake is ready! It looks lovely on the Christmas tree but it would also make a gorgeous gift topper.

You can learn more about working with leather in my previous post

You can learn more about working with leather in my previous post

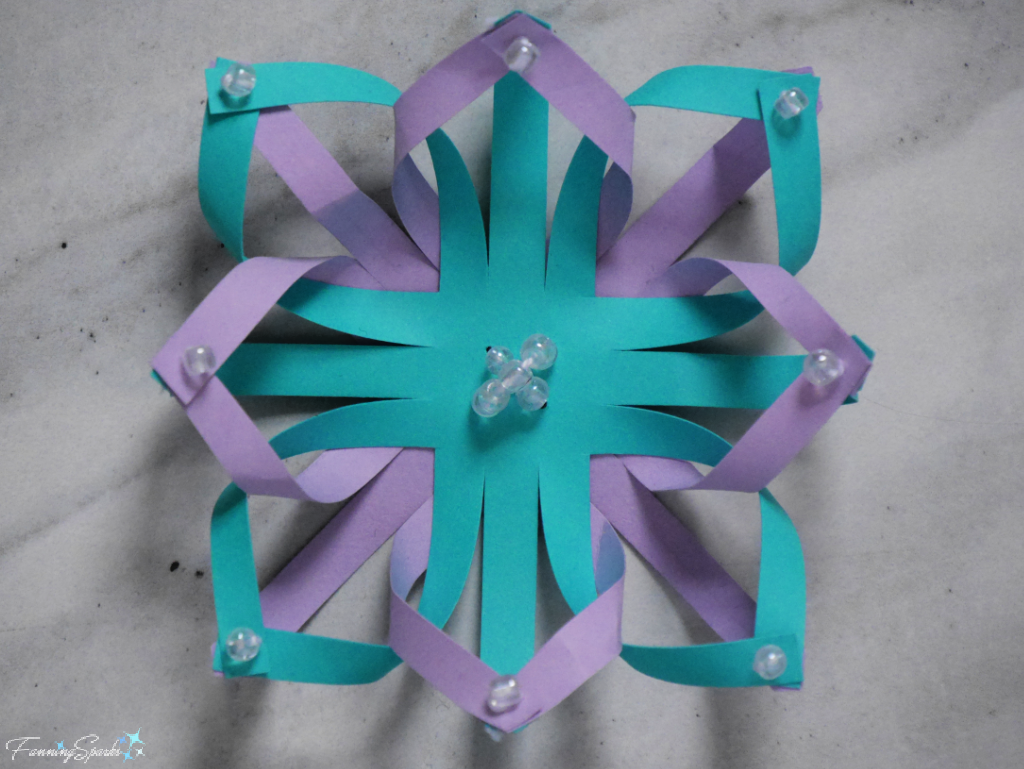

3.

3.

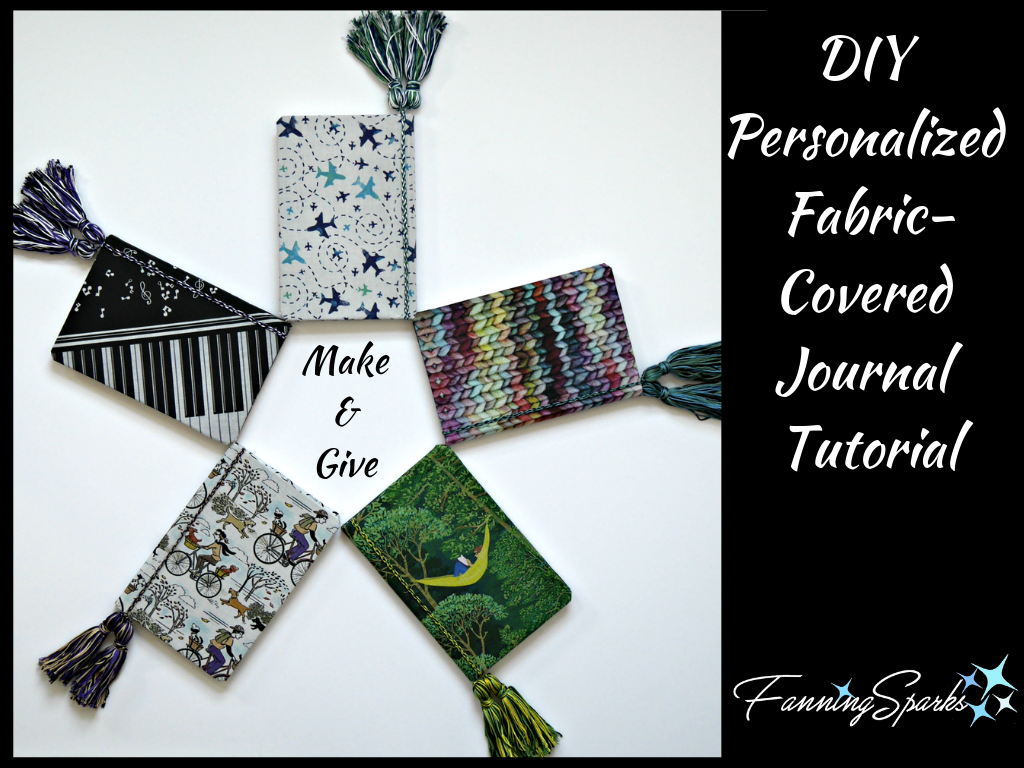

If I were to choose only one make-and-give project from 2019, it would be the fabric-covered journals. I’ve given several to family members and they were well received. It’s an easy project that requires only basic crafting skills. Simply select fabric that reflects the interests of the recipient and then follow the step-by-step instructions provided in the

If I were to choose only one make-and-give project from 2019, it would be the fabric-covered journals. I’ve given several to family members and they were well received. It’s an easy project that requires only basic crafting skills. Simply select fabric that reflects the interests of the recipient and then follow the step-by-step instructions provided in the

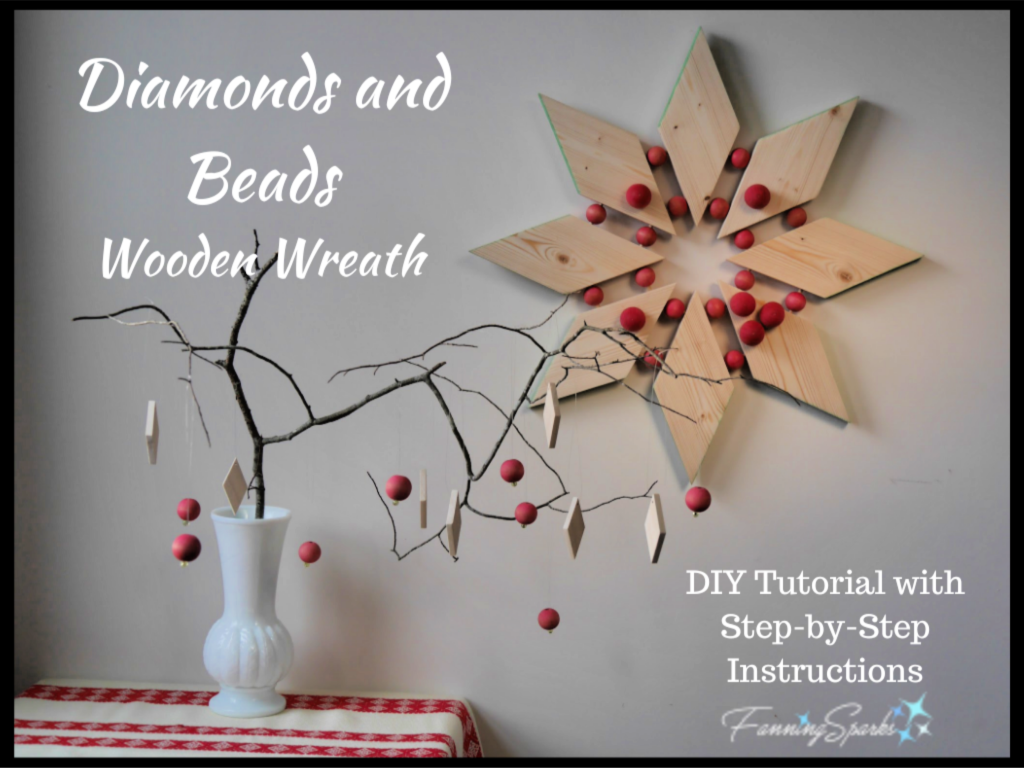

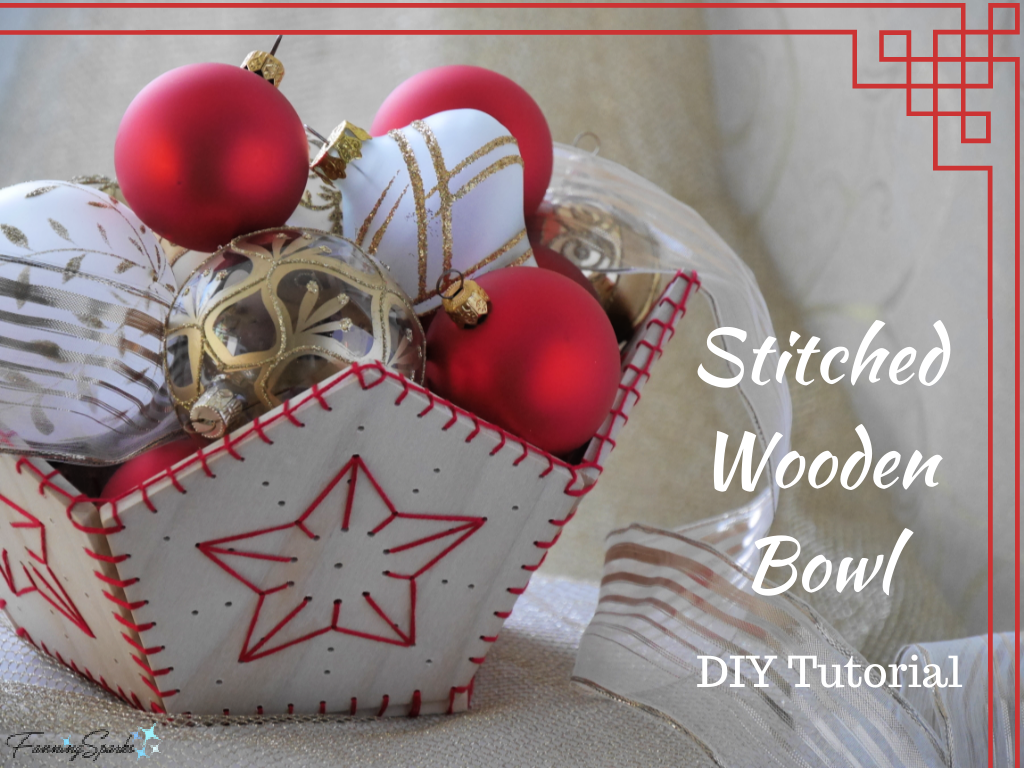

Holiday Decoration

Holiday Decoration

See the post,

See the post,

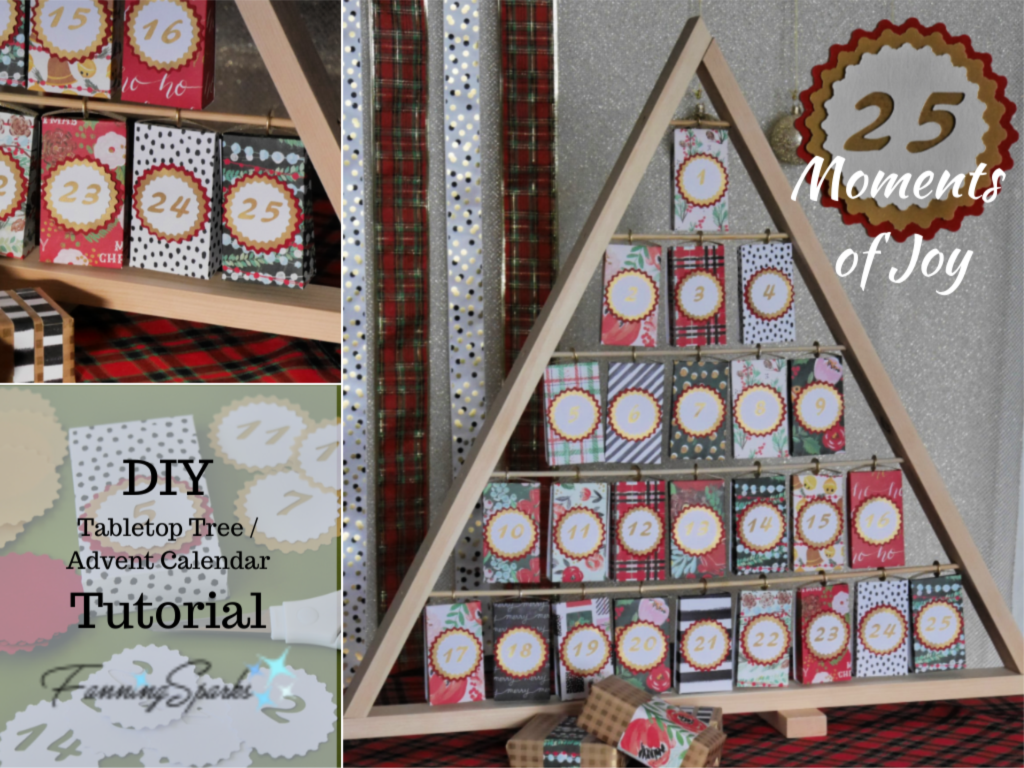

Some holiday decorations are associated with treasured traditions. The advent calendar, for instance, is used to countdown the days to December 25. A few years ago, I created my own version of advent calendar as a gift. Check out the post,

Some holiday decorations are associated with treasured traditions. The advent calendar, for instance, is used to countdown the days to December 25. A few years ago, I created my own version of advent calendar as a gift. Check out the post,

Holiday Traditions

Holiday Traditions