It’s not unusual to stop and reminisce while taking down and putting away Christmas decorations. But this was my first time storing away the miniature glass flamework ornaments I purchased last month and I got completely sidetracked with memories of the amazing town of Lauscha Germany and its rich heritage of glassmaking.

These little glass treasures were created by the talented glass artists at Glaszentrum Lauscha.

By the way, there’s another first in these photos―it’s the first time I staged a photo shoot in snow! We actually had snow in Georgia―something that rarely happens and arrives with great fanfare but never lasts long.

Shown below are the miniature ornaments on the small, 5” tall, flamework glass tree I used to display them―perfect for adding a bit of Christmas charm to my studio!

A repurposed Altoids mint tin was the ideal size for storing these unique ornaments. With a little red felt and some scraps of lace and ribbon, I turned the tin into a storage container worthy of these special ornaments.

The Glaszentrum Lauscha was one of my favorite stops on a recent European Christmas Market tour. See previous blog posts, Postcards from Germany #1, Postcards from Germany #2 and Postcards from Czechia and Austria, for more photos from this memorable adventure.

Described as “The New Glassworks”, Glaszentrum Lauscha has a sizable art glass gallery, a glass workshop, live flamework demonstrations, a restaurant and, unsurprisingly, an extensive shop packed with gorgeous glass Christmas decorations. According to their website, “the new glassworks was built in 2003 … with exactly the old, traditional craft techniques and tools that were used in Lauscha’s oldest glassworks more than 400 years ago”.

Shown below are a few of the beautiful hand-crafted glass Christmas ornaments on offer at Glaszentrum Lauscha.

But Glaszentrum Lauscha is not the only outstanding glass studio located in Lauscha, Germany. This small town, nestled into a steep river valley in the Thuringian Slate Mountains, is considered the birthplace of glass Christmas tree decorations. Lauscha is, in fact, one of the locations recognized by UNESCO under its Intangible Cultural Heritage program for its “knowledge, craft and skills of handmade glass production.”

In her historical fiction novel, The Glassblower, author Petra Durst-Benning describes a view of Lauscha: “Now she could see the outskirts of Lauscha in the distance. The mountains all around cast their long shadows over the houses that clung to the steep slopes. When the sun shone, the wooden shingles on the rooftops glittered gray and silver, but when the village was in shadow like this, all the houses seemed to be wearing gloomy black hoods.”

Most of Lauscha’s buildings are covered in slate tiles which did indeed give the town a rather somber, gloomy vibe during our visit. But a closer look revealed a variety of interesting patterns and designs.

Never having seen houses covered in slate tiles like this, I was intrigued. “Slate is a fine-grained rock” reports Wikipedia, “derived from an original shale-type sedimentary rock composed of clay or volcanic ash through low-grade, regional metamorphism. …

Early workings tended to be in surface pits, but as the work progressed downwards, it became necessary to work underground. … Large slabs of rock were removed from the chamber, typically on railway wagons, and taken to the mill. The slabs were first sawn to the required size, then split to specific thicknesses – this was done by hand for many centuries using a chisel held at a specific angle to achieve a clean split while maintaining the material’s integrity. Finally, the corners of each piece were beveled to allow water to flow over the slate once in place…”.

Evidence of this history can still be found in Lauscha.

The hard, dull, rough slate tiles are a fascinating juxtaposition to the delicate, shiny, smooth glass Christmas ornaments for which Lauscha is famous.

In the heart of Lauscha, a giant, red, metal-framed Christmas ball commemorates “the first glass hut in the region [which] once stood at the Hüttenplatz in the center of Lauscha.” As explained on the website of the Museum of Glass Art Lauscha, “the first glassworks were attached to monasteries, which mainly needed window glass for their churches and vials for medicine. They were traveling huts that only existed for a short time and moved their location when the surrounding forest was cleared. It was not until the 16th century that villages were established around glassworks. … In 1597, Lauscha was added [and] … then played a central role for Thuringian glass … and still plays a central role for artistically designed glass.”

The Museum’s website elaborates “the Thuringian Forest is one of the most important glass regions in Central Europe. Glass has been produced here since the 12th century. Here, glassmakers found all the materials they needed for their trade: wood from the forest to fire the furnaces, quartz sand as the main component of the glass, limestone for hardening and beech wood for boiling the potash as a flux to lower the melting point of the glass mass. Clearing and reforestation, sand pits and water mills have become defining elements of the landscape. Nature and glass culture are inextricably intertwined here.”

We had the good fortune to explore Lauscha’s outstanding Museum of Glass Art (Museum Für Glaskunst) during our visit.

In addition to providing a comprehensive history of glassmaking in the region, the Museum of Glass Art traces the origin of glass Christmas tree decorations back to the production of pearls (hollow glass beads).

The glass tubes manufactured by the local glassworks were the most critical component for pearl production. “With the start of lamp glass blowing around 1755, the cottage industry … found its way into Lauscha.” explains Dr. Gerhard Greiner Bär on the Lauscha Glass Art website. “The production of hollow glass beads in front of a lamp was very laborious. The glassblower used a so-called boot tube, through which a stream of air was passed through an oil flame, creating a jet of flame in which the glass tube was heated and inflated into a pearl using breath. Later, the so-called ‘goat sack’ and then the bellows were used to generate air. After 1867, the oil lamp was replaced by illuminating gas.”

Pearls made in Lauscha were sold around the world for making jewelry. The museum exhibits several mid-19th century sample cards with pearls, in different colors, sizes and shapes. “For a long time, hollow glass beads were the main source of income for local lamp blowers.”

“By the late-18th century, demand had peaked and Glashutten were dotted throughout the town, producing drinking glasses, bottles, beads and, by 1835, glass eyes for doll makers and taxidermists.” reports Jonathon Foyle in a Dec 2014 Financial Times article.

Meanwhile “German traditions were widely exported, and principal among them was the Tannenbaum — the Christmas tree. One was apparently recorded in 1419 as a marketing triumph of the bakers of Freiburg, an arboreal sampling station in the city square, laden with nuts and baked goods for children to pick.” Trees hung with “bunches of sweetmeats, almonds, and raisins in papers, fruits and toys” started to catch on.

“According to legend”, explains an exhibit card at the Museum, “it was a poor glassblower who could not afford expensive nuts and apples as tree decorations and made them out of glass. Whether the story actually happened is not known. It is documented that glass nuts and balls were also made from the production of glass beads.”

There’s an interesting overlap between this legend and The Glassblower novel. In the story, Marie, one of the novel’s heroines, overcomes numerous obstacles to teach herself to blow glass and experiment with new innovative glass creations. At one point, she seeks advice from Peter, an accomplished glassblower and family friend.

“‘I’d like to try something new. It’s still Christmas decorations, but it’s nothing that I’ve ever tried before,’ she said, spreading out the drawings on the table.

‘Walnuts, hazelnuts, acorns. And pinecones.’ Peter looked at her. ‘I don’t understand. This isn’t new. Practically everyone gathers them in the woods and gilds them to hang on their Christmas tree.’

Marie grinned. ‘But not everyone has nuts made of glass hanging on their tree.’

‘Nuts made of glass?’ He looked at her appraisingly.

She grew more excited as she explained her idea to him. She could see every detail in her mind’s eye, could feel the nuts’ smooth curves in the palm of her hand, could run her fingertips over the pinecones.”

Perhaps the early glass nuts and fruit looked like those pictured below. According to the accompanying Museum exhibit card, these were “made in Lauscha around 1900-1920―Free in front of the lamp and blown into the shape. Painted, partly sprinkled.”

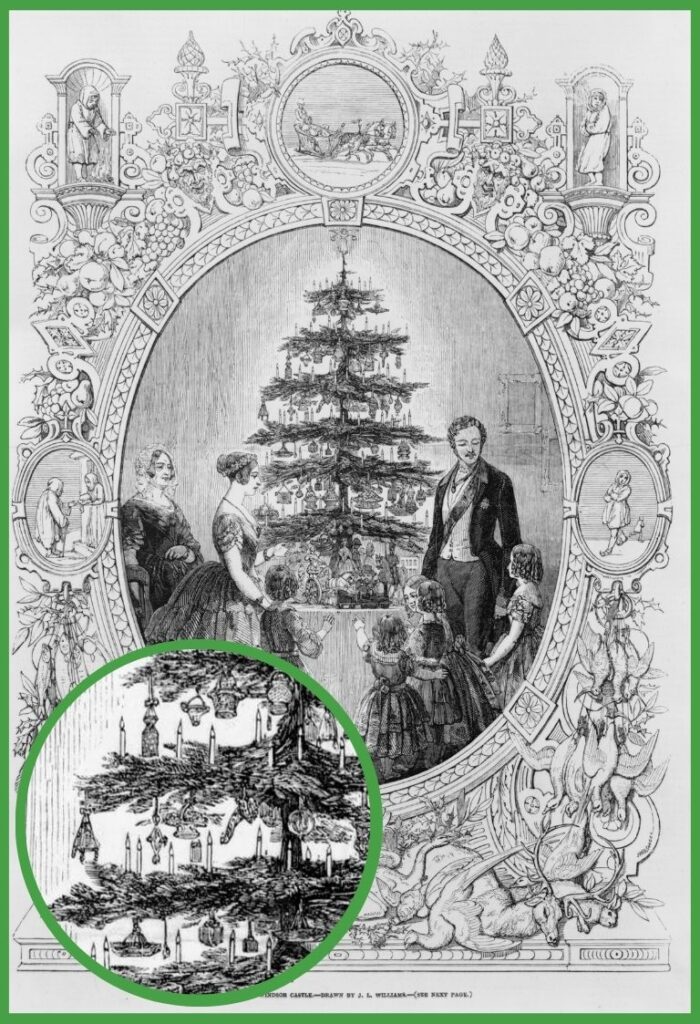

“The earliest surviving entry for an order for “Christmas balls” dates from 1848.” reports the Museum. Interestingly, according to the Victoria & Albert Museum website, this was the same year “the Illustrated London News published a drawing … showing Queen Victoria and Prince Albert… celebrating around a tree bedecked with ornaments. The popularity of decorated Christmas trees grew quickly, and with it came a market for tree ornaments in bright colours and reflective materials that would shimmer and glitter in the candlelight.”

“From 1870 onwards, the balls and molded items were mirrored on the inside with silver nitrate.” explains the Museum of Glass Art. “The production of Christmas tree decorations in Lauscha and the surrounding towns began to flourish from 1870 onwards. Around 1880, the American Woolworth discovered the Lauscha products and organized their export to America. This marked the beginning of the triumph of glass tree decorations. By 1900, almost the entire range of forms of the dazzling decoration was available.”

The Museum displays a fascinating variety of vintage Christmas ornaments such as these from around 1925.

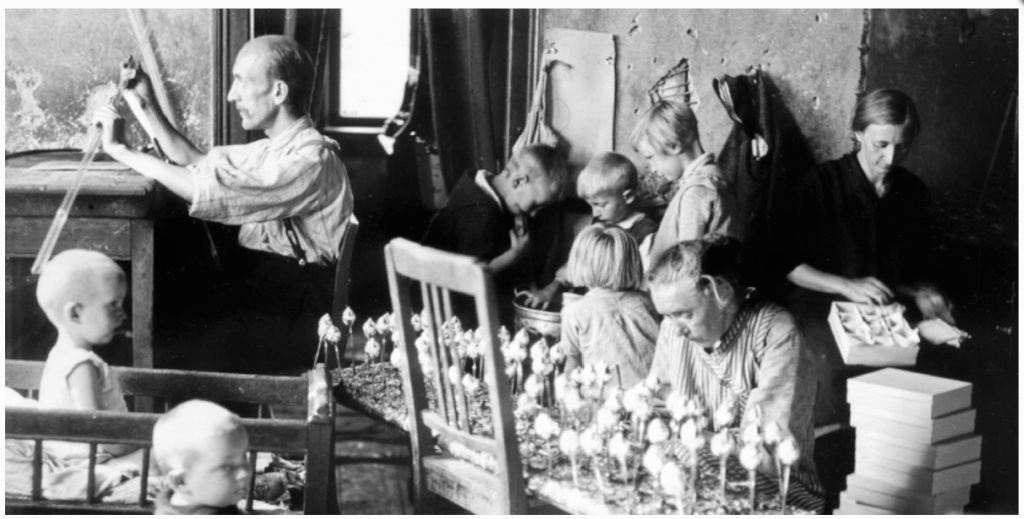

“Glass Christmas tree decorations were traditionally mouth-blown and made entirely by hand at home. All family members helped. The men blew the glass. The women silvered, decorated and packaged. Even the children were called upon. A rather traditional division of labor in which the young people learned their future craft. The houses of the glassblower families were both a workshop and a home.”

At the Museum, a reconstructed glassblower workroom along with an enlarged photo of glassblower Arno Weschenfelder and his family, circa 1925, help visitors visualize the setting.

In contrast, the Museum also features a modern artist glass workshop.

Modern art glass works, such as the vases and sculpture shown below, are sprinkled throughout the Museum’s facilities.

Now, to close the loop on The Glassblower, the historical fiction novel by Petra Durst-Benning, which I’ve mentioned a couple of times in this blog post. The book was first published in German in 2003. It was translated into English by Samuel Willcocks and published in 2014. By happy coincidence, I first learned about the German mountain village of Lauscha while reading this book. The story is set in 1890 and glassblowing plays a big role. From the official book summary: “In the village of Lauscha in Germany, things have been done the same way for centuries. The men blow the glass, and the women decorate and pack it. But when glassblower Joost Steinmann passes away unexpectedly one September night, his three daughters must learn to fend for themselves. … it is dreamy, quiet Marie who has always been the most captivated by the magic and sparkling possibilities of the craft of glassblowing. As the spirited sisters work together to forge a brighter future for themselves on their own terms, they learn not only how to thrive in a man’s world, but how to remain true to themselves–and their hearts–in the process.” It’s the ideal read for anyone planning a visit to Lauscha!

More Info

Previous blog posts mentioned in today’s blog post include:

. Postcards from Germany #1

. Postcards from Germany #2

. Postcards from Czechia and Austria.

The Glaszentrum Lauscha is located in Lauscha, Germany. Described as “The New Glassworks”, it has a sizable art glass gallery, a glass workshop, live flamework demonstrations, a restaurant and an extensive store. See the Glaszentrum Lauscha website for more information.

The Museum of Glass Art (Museum Für Glaskunst) is located in Lauscha, Germany. It showcases a unique and important collection of glass products from Lauscha and the Thuringian Forest as well as presenting the development from pearl production to the manufacture of Christmas tree decorations. See the Museum of Glass Art Lauscha website for more information.

The following resources were consulted in writing this blog post:

. The Glassblower by Petra Durst-Benning which is available here on Internet Archives

. Germany’s Nationwide Inventory of Intangible Cultural Heritage website. The UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage program goes beyond monuments and collections of objects to recognize the importance of “traditions or living expressions inherited from our ancestors and passed on to our descendants. … While fragile, intangible cultural heritage is an important factor in maintaining cultural diversity in the face of growing globalization. An understanding of the intangible cultural heritage of different communities helps with intercultural dialogue, and encourages mutual respect for other ways of life.”

. Lauscha Glass Art website including the PDF of The Trail of Glass Beads – Lauscha Pearls article by Dr. Gerhard Greiner Bär (in German)

. The Business of Baubles — and the Town that Invented Them Dec 2014 Financial Times article by Jonathon Foyle

. Victorian Christmas Traditions article on the Victoria & Albert Museum website

. Christmas Tree at Windsor Castle, drawn by J. L. Williams. Illustration for The Illustrated London News, Christmas Number 1848 which is available here.

. various Wikipedia entries.

Today’s Takeaways

1. Artists in the town of Lauscha, Germany has been making glass for over 425 years.

2. The UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage program goes beyond monuments and collections of objects to recognize the importance of “traditions or living expressions inherited from our ancestors and passed on to our descendants”.

3. Settings in books or movies, whether fictional or factual, can inspire and inform unique travel destinations

Comments are closed.